The case of the missing kōkopu

It‘s hard to believe that common native species like whitebait could go extinct. Especially when they seem to be so numerous species and whitebaiters are catching them by the bucket-load every spring all across New Zealand.

But the whitebait catch isn’t just made up of of one species, it actually includes five – giant kōkopu, banded kōkopu, shortjaw kōkopu, inanga, and kōaro.

Four of the five species caught in whitebait are threatened (Infographic by Stella McQueen).

Four of those species, including the most commonly caught inanga, are classified as threatened. It has even been predicted that those four species could be extinct by 2050, a mere thirty-odd years away. But is it really possible for such a seemingly plentiful fish to decline so rapidly?

New Zealand’s Freshwater Fish Database

Freshwater scientists have an excellent understanding of where native fish are found, thanks to the New Zealand Freshwater Fish Database (NZFFD).

This searchable repository uses data from around 40,000 fish surveys done all over New Zealand, most dating from the 1980s onward.

A bluegill bully caught during a stream survey in Lower Hutt (Photo by Kimberley Collins).

Freshwater scientists are continually using this database to better understand our native fish and the places where they live.

The records have been submitted by a huge variety of organisations, including NIWA, DOC, universities, councils and environmental consultancies, and they can be accessed by anyone.

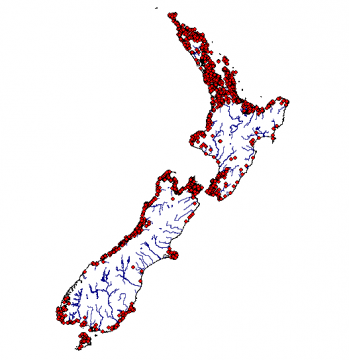

A map showing all the data points registered on the New Zealand Fish Database.

Catchments around New Zealand have been so thoroughly surveyed that only the real gaps in our knowledge are in the most remote or inaccessible streams.

It is easy to use the database to generate maps showing all the places where a species was found, and is found. So let’s use it to look at the least threatened of the species caught in whitebait, the banded kōkopu.

What about the banded kōkopu?

Banded kōkopu distribution over New Zealand.

Of the five whitebait species, the banded kōkopu is the only one that is not listed as threatened.

Despite this, banded kōkopu have gone from being “quite common” to virtually extinct across a large region of New Zealand in the last seventy years.

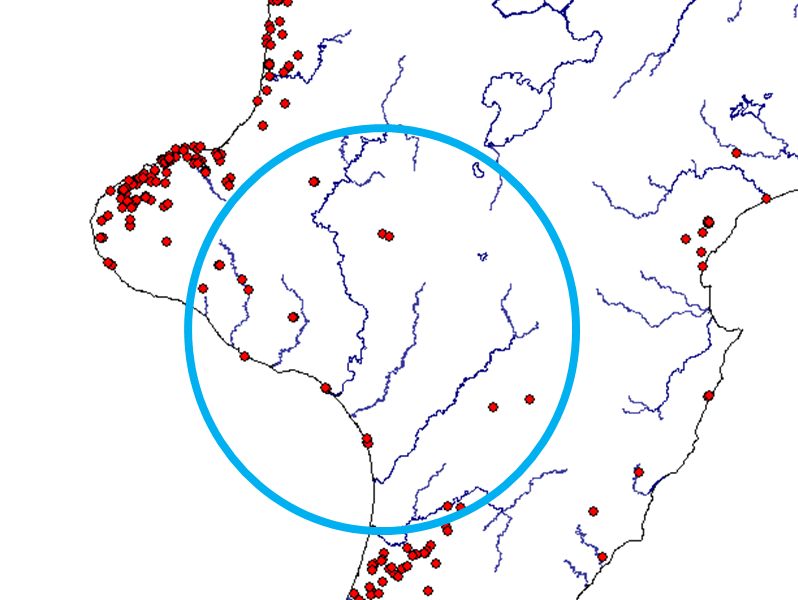

Between south Taranaki and the northern banks of the Manawatu River there are very few records of banded kōkopu, despite the regions being heavily surveyed.

Most of the records in this area are of single fish and a couple of landlocked lake populations that don’t contribute to the whitebait catch. The only recorded, healthy, migratory population is in a short, man-made ditch on a Whanganui beach.

Banded kōkopu distribution in the Manawatu-Whanganui region

It is not uncommon for there to be natural gaps in a species’ distribution. It could be due to less-than-ideal habitats or local extinctions thanks to natural events like volcanic eruption and glaciers.

What makes this regional decline in banded kōkopu unusual?

The first thing to tell us this gap may not be natural is that the Manawatu lowlands used to be covered in swamp forest. This is perfect banded kōkopu habitat and the region would have been absolutely teeming with them.

A banded kōkopu (Photo by Stella McQueen)

Following the drainage of these wetlands, the kōkopu have almost completely vanished from this area. They are holding on in lowland waterways in southern Manawatu where there are wetland remnants.

The second hint that this gap in banded kōkopu distribution is man-made requires us to go back seventy years and a little north, to Whanganui.

In 1948, a large freshwater fish (pictured) was brought to the Whanganui Museum. Jack Moreland – the natural history curator at the time – had been busily building up the fish specimen collection but had never seen one like this before. He wrote to an expert in Canterbury to try and get an identification.

It is clear from the letters that Jack was very familiar with banded kōkopu, saying that the mystery fish “appears to be a normal specimen” but noted small differences that the casual observer could easily overlook.

The fish was later identified as a giant kōkopu. But because this species is so cryptic and hides away, Jack had never seen one before.

Tucked away in the letters was this line: “the many I have caught in the past have all been of the brown barred variety [i.e. banded kōkopu], which are quite common here.”

Why they have nearly vanished from around Whanganui and the wider area from South Taranaki to Rangitikei is harder to pinpoint than in the Manawatu and its loss of wetlands.

Death by a thousand cuts

As with the declines of many other native fish around New Zealand, it seems likely that it is not due to one cause but rather the ‘death by a thousand cuts’ that happens to waterways thanks to the unsustainable ways we currently choose to use the land. Current efforts to fence streams and reduce nitrogen losses cannot turn the tide of our declining waterways in the face of endlessly intensifying agriculture, more and more water abstractions, and numerous new discharge consents.

This clear loss of a species classed as ‘Not Threatened’ over a broad region within the last seventy years makes the loss of the other four threatened whitebait species over the next thirty years more realistic.

If it weren’t for an old letter tucked away in a museum archive, we wouldn’t know this. How many other losses and declines of our native fish species have been happening under our noses?

Banded kōkopu are doing well in some parts of the country but are clearly quietly vanishing from others. Yet its threat classification remains ‘Not Threatened’. At a time when the vast majority of our native plants and animals are under such serious pressure from human impacts, we can’t get complacent about the ones that are still common. We must remember that a species that is abundant now can disappear in only a few decades.

There is only one native fish that has gone extinct – the grayling. It used to be in astonishing numbers but the population crashed and the last living fish was last seen in the 1920s. Thirty years later, it was given legal protection, and remains the only legally protected native fish despite being extinct.

How late will we leave it before the banded kōkopu – or any other native fish – receives meaningful legal protection?