Re-thinking wetlands

“Hope and the future for me are not in lawns and cultivated fields, not in towns and cities, but in the impervious and quaking swamps.” Henry David Thoreau

I remember many years ago when I was a journalist in Timaru, I was doing some research on the history of an area known as Maori Hill. Then, as now, it was a pretty housing area with nice views of the sea, access to the beach and the city’s largest outdoor swimming pool facility on its tamed and smoothed summit.

But it wasn’t always that way. What I learned from my research was that Maori Hill was so named because it was once a ‘native reserve’. This was wild, uncultivated land set aside by the early colonial authorities to allow indigenous Maori to continue their traditional food gathering after most of the native lands had been purchased – often dubiously – or confiscated and turned into farmland and towns for the European settlers.

Then, Maori Hill was a swampy valley with low, drier hills rising from its sides, the land rolling down to a marshy coast. A slow, stream ran through the middle of it and exited to the sea. The area was thick with wetland plants like harakeke, toe toe, swamp tussocks, native herbs, shrubs, reeds and grasses. Coastal trees would have been there too such as kowhai and ribbonwood and, in the wetter areas, the tall and majestic kahikatea. The drier tops probably hosted manuka, kanuka, red-flowered rata and the mighty totara. Twisted tangles of wind-bent coastal coprosma and cutty grass would have made parts of the valley almost impenetrable.

Here Maori gathered harakeke leaves for breaking down into fibre for weaving, harvested stout manuka poles for buildings and tools, and gathered reeds for thatch for their whare (houses). The stringy ribbonwood and totara barks were useful too for ropes, baskets and to make shelter, and a perhaps a few larger trees were felled over generations for carving waka (Maori canoes).

Food was gathered here too. Oral histories record seasonal gathering of inanga (whitebait), tuna (freshwater eel) and piharau (lamprey eel). Weka, kereru, waterfowl and other birds would have been taken for the pot, as were the berries and fruits of shrubs and trees, the heart and roots of ti kouka (cabbage tree) were steamed and numerous other plants were used for food and medicine. Fish would have been harvested from the sea and the tidal marshes.In short, this low-hill-and-wetland environment was a supermarket, a clothing shop, a hardware store and a pharmacy all in one.

But it wasn’t to last. Timaru was a popular pioneer town, growing rapidly, and the white folk jealously eyed the potential of the land that, in their eyes, was ‘going to waste’. Letters to the editor of the Timaru Herald were written bemoaning the fact that the Maori were wasting the ‘gift’ (of their own land!) by not clearing and cultivating it. “If they will not do something with these swamps, it must be given to the industrious settler to drain and make proper use of,” one correspondent wailed.

Which is exactly what happened. Using a law that said Maori reserves could be confiscated if Maori failed to ‘make use of them’ (i.e. clear, fence, drain plant and harvest them) Maori Hill was taken, drained, cleared, cultivated, reshaped and piped and generally ‘civilised’ for the settlers’ purposes. The historic records are sketchy as to what happened to the Maori who had depended on that reserve for their food and supplies.

Ironically Timaru now fights to save its remaining wet areas – including Otipua wetlands on the southern edge of the city

I tell this story not to reflect on the attitudes of the colonial powers toward the culture of New Zealand’s indigenous people, but as an example of something else that the settlers brought with them that still impacts on New Zealand today – a strong dislike, almost fear, of swamps, marshes and bogs. Wetlands were wild places to be avoided, at the least, or, preferably, places to be cleared, drained and tamed in order to be made ‘useful’. Or they were seen as waste ground; places where the growing population could throw its rubbish and dispose of its sewage.

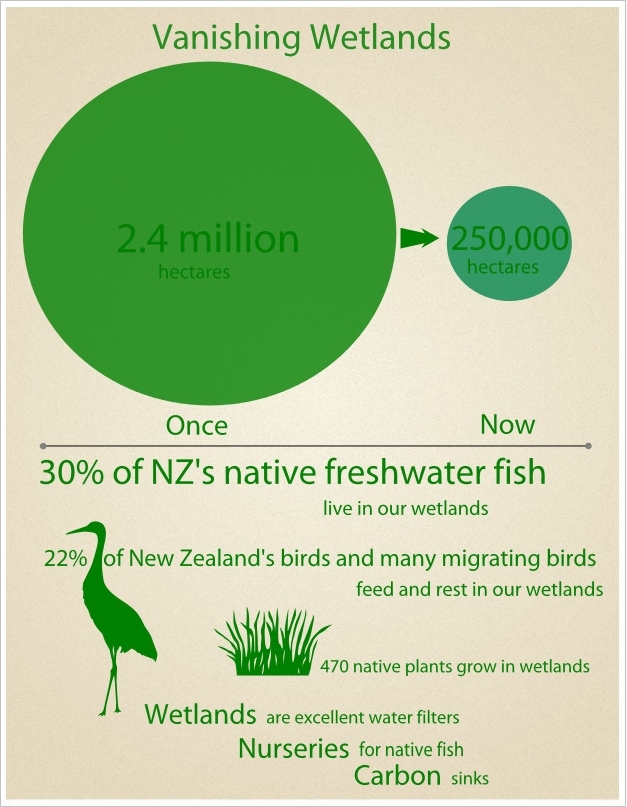

This attitude toward wetlands has persisted through generations. The great majority of the wetlands in New Zealand that existed in pre-European times, have since been lost to clearing, drainage and development, or by being turned into landfills. Very few remnants of eastern plains and coastal wetlands remain. The most untouched wetland areas are those that are fortunate enough to be in places that were deemed too difficult or too isolated to be attractive to the farmer or developer.

‘In places too difficult or isolated, wetlands survive’

Even today local authorities regularly receive resource consent applications for wetland drainage for housing development or to turn into land for farming or industrial purposes. Fortunately, councils today have a very different attitude than those worthy gentlemen of Timaru Borough all those years ago. It is much more difficult to get permission to ‘kill’ a wetland today, but it does happen.

For instance, one of the jewels of Christchurch’s natural resources is the Travis Wetland. It is much celebrated as a nationally significant wetland, home to numerous species including some very rare native plants, birds and fishes. But only a few years ago much of this precious swamp was earmarked for draining for a housing subdivision. It took intense lobbying and activism on a large and persistent scale to finally persuade the city leaders to refuse the development consent and set Travis wetland aside as a nature heritage reserve. It is far from pristine, being partially choked by willows and other introduced plant pests, and open to the predation of introduced animal pests such as rats, feral cats and stoats. But pest control of weeds and predators is underway, as is an intensive planting and management programme; all of which is paying off; the native species are recovering.

I wonder at the root cause of this persistent antipathy toward wetlands. It certainly doesn’t stem from Maori culture, which saw them as larders and cultural material banks. And our own European ancestors were once hunter gathers too; people who would have made use of the wild lands in the much the same way as Maori.

Perhaps though, with the development of agriculture, which brought an end to nomadic lifestyle for most peoples, and the growth of towns and cities, mankind began to lose touch with the wild places. Land that could not be planted and harvested was deemed a waste. Hungry cities demanded more fields to grow food. Wetlands were seen as dangerous too. Bogs claimed people to be never seen again. In northern lands they harboured dangerous animals; dangerous humans too, they were great places for criminals and rebels to hide (America’s Swamp Fox comes to mind).

And so we seem to have developed a cultural antipathy toward wetlands that is almost pathological. Swamps attract names like ‘dismal’, ‘despair’ and ‘despond’. They are inevitably evil places in fiction – Conan Doyle subjects his characters to fear and death in the deadly bogs of Dartmoor (The Hound of the Baskervilles), and Tolkien has Frodo almost die of despair in the dead marshes (Lord of the Rings).

Thoreau’s attitude (quoted above) was unusual.

Even today, studies show that people gain inspiration from light-filled forest, mountains, plains, lakes and sea. Few people place swamps on their list of places to go for solace, healing and inspiration. Bogs, swamps and marshes, like caves and dark and damp old forest, are more likely to feature in the imaginations of our fears.

But, thankfully, there is a growing appreciation of the beauty and the biological importance of wetlands.

Thoreau was a pioneer and exemplar of this attitude. He said: “When I would recreate myself, I seek the darkest wood, the thickest and most impenetrable and, to the citizen, most dismal swamp. I enter a swamp as a sacred place, a sanctum sanctorum.”

And in that sentiment Thoreau and I are soul brothers. I have written before of my childhood love of the wild world of wetlands.

And, it must continue on a global scale! There is much truth to the old conservation adage “think globally, act locally”. But the modern world requires us to also act globally through the power of such mediums as the Internet and international media.

For we cannot be alone in this. Consider the Heathcote/Avon estuary, or the magnificent Manukau harbour, alive with thousands of kuaka (godwits), plovers, knots and other migratory birds. These birds traverse the globe in their migratory routes, stopping at wetlands along the way, wetlands that in many countries are under even more threat of development and desecration than our own.

Will the day come when our wetlands are silent, the voice of the kuaka no longer heard, because while we have fought for our own marshy spots we have ignored the fate of those in countries far from our own?

Global action is a vital component in the battle to save our wetlands. Get to know your local wetland and while you’re at it, read more about the recent RAMSAR conference on this global issue. http://www.birdlife.org/community/2012/07/wise-decisions-wetlands-ramsar-cop11-begins-bucharest/