Box of Birds

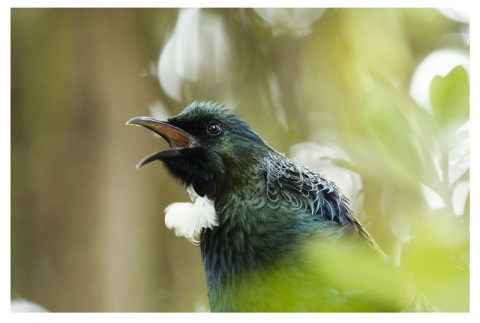

Rambunctious. Confused. Operatic.

The spirited call of the tui with its clicks, coughs, wheezes, bells and whistles has been pinned with many an adjective. And now a scientific study has proven one of them to be true: elaborate.

The very first study into the tui’s song has revealed that it song ranks as one the bird-world’s most complex.

Massey Conservation Biology Masters student, Sam Hill, recently took a 2.5 hour sample of tui song, and discovered that it contained over 300 different ‘songs’ (a series of newly detected notes).

This places the tui amongst a handful of birds that can produce over 300 songs, such as the nightingale.

It’s a far cry from more skilled songsters, such as the brown thrasher (1000 songs), however Hill is confident further sampling will prove the vast breadth of the tui’s song.

The 33 year old British born birder is one of the first people to study the tui’s song, which he concedes is surprising given that it’s one of New Zealand’s most popular birds (the tui was voted Bird of the Year in 2005)

One of the reasons he believes no-one has tackled this research is because it would have been prohibitively labour intensive.

It is only in recent years that sound equipment, such as spectrograms, has caught up with the complex task of analysing bird song.

Hill’s investigation into the tui’s song is part of a growing body of research into song creation and dialect of birds such as the kokako and saddleback.

International research has shown that there are two types of songbirds: closed and open learners.

Closed learners, such as stitch-birds and whiteheads, learn their song in their first few weeks and it remains unchanged through its lifetime.

In contrast, open ended learners like our tui and song thrushes have a song that evolves over time. Rather just imitate their parents, they sample elements from their sonic environment and sew it into their song.

Indeed, researchers have shown that song thrushes have picked up a ‘kiwi twang’ in areas abundant in kiwi. And numerous anecdotal reports have indicated that the tui’s song improves in the company of bellbirds. Also well known, is the tui’s ability to reach outside the forest sphere to take city sound bites of such things as pizza jingles and cell-phone rings.

The organ that produces this song is the syrinx, which is the equivalent of our larynx, however it lies further down the wind pipe, at the point where the windpipe divides into two bronchial tubes.

Songbirds, such as thrushes, canaries, cardinals and the tui (passerine birds ) have nine pairs of muscles to control the syrinx’s tautness.

The tui is unique in that it can fine tune the airflow coming from each tube, so that either side is open or closed, which means it can ‘duet with itself’.

It can produce a range of sounds from gravely, guttural notes to shrill ones almost simultaneously. Indeed, its operatic range is so vast, some of its song is ultra-sonic.

It’s highly likely that you have caught yourself watching a tui in full throttle, beak agape – and yet you can’t hear a squeak. That’s because parts of the tui’s song is inaudible to us. How much is debatable, however Hill estimates that it’s a ‘fair proportion’.

Although birdsong has many functions, one of its major tasks is to attract a mate. And, well, innovation is sexy.

Females seek mates with long, complex songs because this is an indicator that he’s genetically fit (disease-free), anatomically sound, and intellectually capable of composing complex symphonies.

A recent study of zebra finches showed that if a male was missing a couple of syllables, they’d have almost zero luck with the ladies.

Hill’s research compared the dialect mainland tui (Tawharanui Regional Park) to that of the Chatham islands.

He analysed various aspects of the sound, and teased out what he describes as energy-expensive trill in the male’s calls using a spectrogram.

Trill has a very specific audience: females, and a very specific effect. It is one of those ‘sexy syllables’. The findings were conclusive. Themainland tui’s song (song sample) was not only longer, it was filled with more trill.

Hill believes greater competition amongst mainland tui pushed these males to produce sexier and sexier songs. But population size is not the only factor at play though. Hill thinks habitat may also dictate the song type.

Hill says trill-filled song is beneficial to mainland tui – because it carries well over open spaces such as farmland. Whereas, the Chatham islands* tui (song sample) have no need for trill because their land is largely forested.

Although he’s spent almost a year studying the tui’s song, Hill still has a head full of questions which he hopes to answer in the near future.

And he’s somewhat ambitious. With more field study he believes he can launch this NZ tweeter into the international limelight. Here’s hoping.

• Pitt island and South East Island