Bird of the Year soars to new heights in 2019

By David Brooks

By David Brooks

Bigger and better than ever, our Bird of the Year contest had it all in 2019. Relentless mockery between campaign teams, a neck-and-neck race to the finish line between two flightless treasures and priceless publicity for our native birds and the threats they face.

Nearly 43,500 New Zealanders voted between October 28 and November 10. They had fun and learned more about our amazing native birds and their quirky habits.

Bird of the Year is also a valuable opportunity to challenge many New Zealanders’ misconception that nature is doing okay in New Zealand and to remind them more than three-quarters of our native birds are threatened with or at risk of extinction.

The hoiho, or yellow-eyed penguin, headed off the kākāpō to be crowned Bird of the Year in 2019. The win was well deserved recognition for one of the world’s rarest penguins and for its dedicated campaign team which worked hard to rally support, including the current and former Dunedin mayors and legendary Dunedin band The Chills.

After the win, many media in New Zealand and overseas carried stories about the plight of the hoiho. These would not have been written without the Bird of the Year competition.

Unlike 2017 and 2018 there were no scandals over attempts to rig the voting by misguided fans of a particular bird. But just as the buzz over the hoiho’s victory was starting to die down, a brief media frenzy erupted over suggestions of Russian interference in the election.

Unlike 2017 and 2018 there were no scandals over attempts to rig the voting by misguided fans of a particular bird. But just as the buzz over the hoiho’s victory was starting to die down, a brief media frenzy erupted over suggestions of Russian interference in the election.

Suddenly our yellow-eyed champion was being drawn into the same kind of controversy surrounding a yellow-crowned world leader.

It started with an innocent observation that there had been some interest from Russians in Bird of the Year. Only 196 valid votes out of more than 43,000 came from Russia but it was enough to attract the attention of foreign media including the Washington Post, the Guardian and the Moscow Times.

The Russian paper showed a photo of a hoiho with a Russian flag clamped in its beak and the foreign headlines included “New Zealand twitchy amid claims of Russian meddling in bird of the year contest” and “Russia accused of meddling in New Zealand bird of the year vote”.

The New Zealand and global media interest keeps growing every year following a modest start for Bird of the Year in 2005. In those pre-social media days a total of 865 votes were cast in the first competition, with the tūī coming out on top.

Social media is crucial for the competition now, providing this year’s 71 campaign teams with the perfect platform to sing the praises of their own birds and to fling mud at rivals. Runner-up, the kākāpō, was derided as a moss chicken and a boomer, and the hoiho was described as the bird most likely to take a date to McDonalds for a filet-o-fish. Australasian bitterns were credited with being the bird most capable of imitating a stick.

The competition took another leap forward in 2019 with the introduction of the single transferable vote (STV). Voters could rank up to five of their favourite birds, so if their favourite bird was eliminated from the competition in later rounds of voting, their subsequent preferences could also be taken into account.

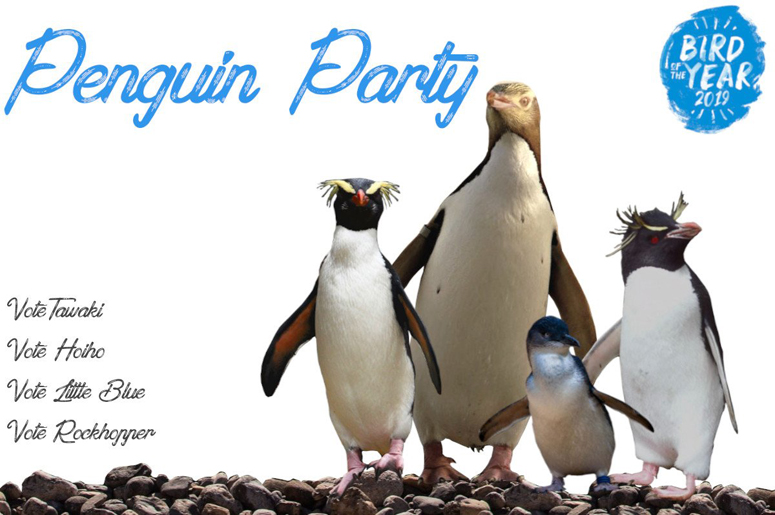

This led to some new tactics, such as enterprising campaign managers for the four species of penguin in the competition setting up a penguin party to back each other for second and subsequent preferences. The pōpokatea/whitehead, miromiro/tomtit, totowai/NZ robin and black robin also formed a small bird alliance.

Although the hoiho was well ahead in first preferences after the first week of voting, the new voting system meant that the kākāpō was in front until near the end because of other preferences. When voting ended, third spot went to the kakaruia (black robin), followed by the tūturiwhatu (banded dotterel) and pīwakawaka (fantail).

So that’s it for another year. But some enterprising bird fans will already be cooking up ideas to win the crown for their favourite bird in 2020.