Native Frogs are Cool (Literally!)

In September last year, the Frog Lab group at the Department of Zoology (University of Otago) had the privilege of hosting the Kiwi Conservation Club for part of the day. We wanted to help them learn more about New Zealand’s very own rare native frogs and get up close with some that we have in captivity.

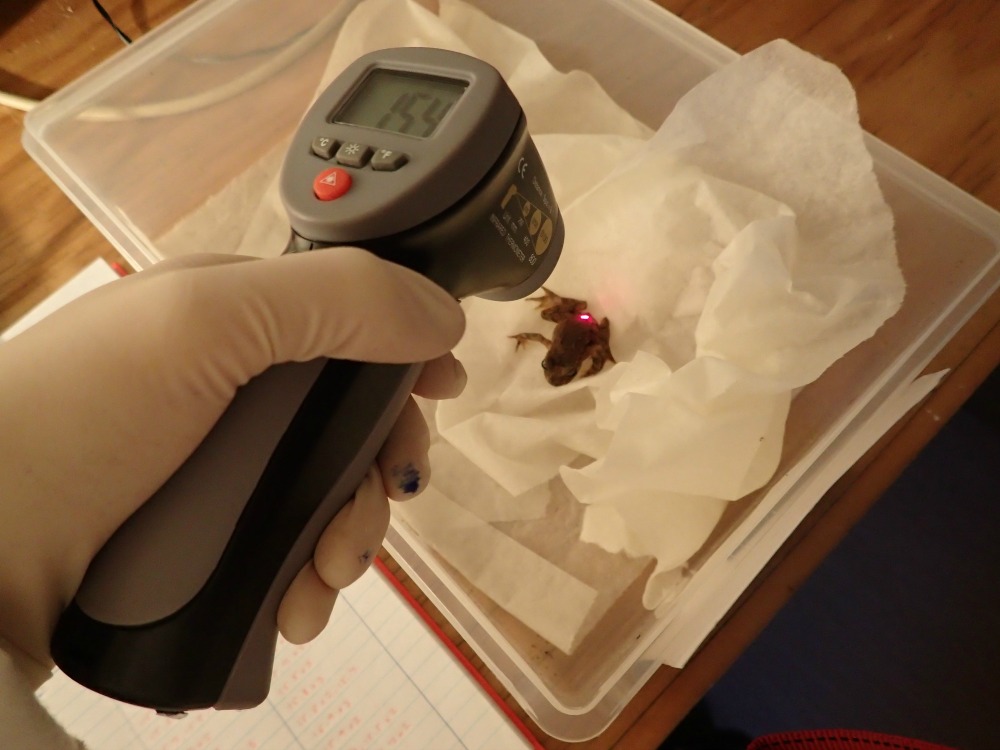

At the time, I was running an experiment with the Hochstetter’s (“Hock-steer-Ters”) frogs to find out whether Dunedin’s own Orokonui Ecosanctuary would be a good home for them. Since it is rather cold here in Dunedin, and Hochstetter’s frogs come from the North Island, the first thing I needed to do was see was whether they could cope with the cold.

My experiment was a simple one – cool them down and see how they responded. So at a balmy 6-7.5˚C, I looked at how long it took them to digest food and kept a very close eye on their overall health. It turned out that, although these frogs do prefer warmer temperatures (mainly 15-21˚C), they actually do just fine in cold temperatures.

Photo by Luke Easton

What was really interesting was that some frogs took 41 days to digest food! Even though frogs are ectotherms (which means their bodily functions rely on environmental temperatures), for a small frog, that is pretty impressive! Another interesting discovery was their ability to digest food properly was dependent on what they ate in cold temperatures. Slaters, for instance, were pooped out whole in cold temperatures, but when the frogs were fed prey like crickets, they pooped out, well… normal poos! The ability to digest food is important for energy uptake – if its too hard to digest, your body can’t use it. In the case of the frogs, having a generalist diet (meaning they are not fussy) is great for their survival in cold temperatures.

Photo by Luke Easton

So now we know that adult frogs will likely be fine in Orokonui conditions, but there is one more question to be answered – how does temperature effect development? This is a rather tricky question to tackle as tolerances to certain temperatures are specific to an individual species, and can be specific at the developmental stage too. Embryos in eggs require a certain range of temperatures to develop and eventually hatch, but then tadpoles (or froglets if it is a land-dwelling species that bypass the tadpole stage in the egg) would likely require a different range of temperatures to develop.

Once they reach adulthood, they would probably prefer other temperatures during their lifetime. In the case of native frogs where finding eggs are extremely rare, and the logistics of being able to even take some of these into captivity to rear under different temperatures given the rarity of the species, you can start to see how answering this question is a problem. This is why it is crucial that there are thorough records for the management of native frogs that successfully breed in captivity (e.g. Archey’s frogs at Auckland Zoo). Fortunately, there have also been some recent breakthroughs for breeding Hochstetter’s frogs in captivity. Closely monitoring the temperatures whilst these eggs develop will therefore be a major stepping stone in confirming whether or not Orokonui Ecosanctuary can become a new home for these very special frogs.