Boomerang birds

In New Zealand annually, between 10 -30 of transfers take place each year in an effort to re-colonise our mainland islands with threatened birds – however some birds, just prefer home and will go to great lengths to return to their forest, island or wetland base.

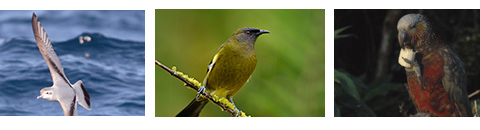

Fairy prion, bellbird and kaka often boomerang back to their source site. Photos: Nick Talbot, Craig Mckenzie, Brent Bevan

There’s the story of the weka who legged it back to Gisborne from Whakatane, the spotless crakes that beat their catching team back home and the little tomtit that was transferred to Tiritiri Matangi only to wing it back to the Hunuas.

Indeed, our wandering kokako “Duncan” – who became a media star in less than a week – strayed almost 31kms from his transfer site in the Waitakere ranges into suburban Auckland.

Since Richard Henry attempted to save kakapo from extinction in the 1890s by transferring several hundred of these gregarious green parrots to Resolution Island, hundreds of translocations have taken place across New Zealand.

Transfers have saved many species, including our little spotted kiwi, buff weka, black stilt, kakapo, South Island saddleback and black robin.

Initially, these were almost solely done by NZ Wildlife Service (later DOC) however since 2000, community groups have taken a lead role, with DOC providing best practise guidelines and some supervision for endangered birds.

Indeed, with all number of community restoration groups putting their hands up for threatened birds, reptiles and frogs the number of translocations has swelled. In 2010, 71% of the translocations were undertaken by community groups either solely or with the assistance of DOC.

We have come a long way since Richard-Henry’s one-man mission. Since then, we’ve transferred 70 species of birds – and steadily, the success rate went from just 15.3% in the 1960s to 66.6% in the 2000s.

One hand raised shore plover was transferred from Mt Bruce to Mana island as part of a Forest & Bird project, only to be found on top of his cage at Mt Bruce trying to get back in! Unlike seabirds, terrestrial birds like the shore-plover undertake a perilous journey through pest riddled areas to return home.

The 30% or so transfers that fail can be put down to many factors but two prevail – difficult birds or a difficult transfer location.

Getting birds to stay in any given area can be hard, but for seabirds at least there are a few tricks that you can employ. DOC’s seabird transfer specialist, Graeme Taylor first started transferring diving petrels back in 1997.

Over three- years, from 1997 – 1999, he transferred 240 chicks aged from one week old to birds just days off fledging from two source islands to Wellington’s Mana island.After 2-3 weeks they cued into the site features (such as odour, sound, local landscapes and possibly the Earth’s magnetic fields) and began to ‘imprint’ on this new site.

Soon after being transferred to the island, the birds would then head out to sea – and at the time of their predicted return, researchers would broadcast their calls over the sea and wait and wait in the hope they would remain faithful to their childhood home.

At the start the team lost around 50% of the birds to problems with artificial diets, heat stress, extreme weather events and other factors, however once transfer teams accounted for these factors, the transfer survival rate leapt to over 90%.

In spite of these early losses more than 20 diving petrel chicks returned to Mana Island and started a new colony – a colony that now boasts dozens of pairs.

These tried and true techniques were then then applied to all seabird transfers with much success – although anchoring isn’t always fully successful for certain seabirds.

Indeed, one seabird that is very much in the boomerang category despite all number of settling techniques is the Fairy Prion. In a transfer from Stephen’s island to Mana island of 240 chicks, almost half returned to Stephen’s Island to their very own patch.

The reason for why some birds returned is unknown, but then dispersal doesn’t equal death for seabirds, so now it’s just a matter of playing the numbers game by transferring large volumes of birds in the knowledge that some will stick.

Now that DOC has a decent guidebook for many of the species transfers they largely leave it up to community groups to do translocations however some precious birds require DOC supervision, such as kokako and rock wrens.

Disease, food and predator levels are all factors that can determine whether a bird will stick or bolt and initial research is starting to string together those factors that are important for particular birds.

Independent conservation scientist, Kevin Parker, who has been involved in over 35 translocations of birds says that some sites are hard, and some birds are hard.

Robins and saddlebacks that are transferred onto islands tend to stick, however if they’re put on a mainland island they are more prone to disperse or using green corridors, possibly in an attempt to return to their original site.

Likewise, peninsulas are tricky because the birds move along the edges of the coast.

He says the dangers of these sites are that birds move into seemingly good forest areas, however when they set up to breed and nest, their new family gets munched on by the pests in the area. These areas are termed ‘ecological traps’.

He sums it up in one sentence – “birds don’t read maps”. It’s as simple as that. And for birds such as bellbirds there seems to be little stick-ability regardless of the location. Just last year, one transferee quit pest free Mana Island to visit Zealandia.

They’re strong fliers, so bellbirds are likely to boomerang back to their original location. This is also true for kaka, who sometimes yo-yo between the two sites – especially if there’s a feeding station to keep them (briefly) anchored.

Parker says that although age appears to be a factor with juvenile birds less prone to disperse, some birds just won’t stay.

From initial reports– our rails (19%) and kaka and kakapo (26%) – either don’t stay, or just don’t survive. So which ones look promising?

Our critically endangered fairy tern seems an obvious candidate for transfer given that its breeding sites are competing with large hotel chains.

Already, trial transfers have been done in the USA’s Gulf of Maine on least terns, however the effort & budget required to hand rear chicks is just too much given DOC’s shoestring budget.

Another bird that looks the most promising is the Chatham Island Albatross. And Taylor says within the next couple of years the Chatham Island Taiko Trust will transfer this bird from its sole breeding site – a rock stack – onto the mainland with help from Birdlife International.

Japanese and American conservationists have built up a good body of knowledge around how to transfer albatrosses, and Taylor is hopeful this will inform the transfer of these formally unmoveable birds.

Unlike diving petrels, albatross require 3-4 months of parental care and they’re surface nesters, so they have a good chance to take in the scenery before they depart for the high seas.

The point at when everything clicks in place, and they say to themselves – “I know where I am” is still very much unknown, so Taylor says transferring the chicks at a young age and hand-rearing them with sardine smoothies until they feel at home is key.

As opposed to seabirds, many terrestrial birds in NZ have been attempted, and those 50 bird species that have yet to be transferred to form a new population elsewhere either have no equivalent habitat, or simply are able to do their own transfer (i.e naturally re-establish within their historical range).

Indeed, with bird translocations reaching fever pitch (there were 29 just last year) and restoration groups gunning to create their own ark, we may see groups looking beyond feathery immigrants.

Less glamorous species such as weta may creep up the wishlist, and so far, there have been few reports of wayward weta, so re-homing maybe hassle-free?

Taylor has a cautionary tale around transferring snails though – one tagged Placostylus snail was moved to a safe, pig free site, only to slip under the fence to its much-loved hangehange bush 100 metres away – so even snail boomerang!

Reference: Conservation Translocations of New Zealand Birds, 1863 – 2012, Colin Miskelly and Ralph Powlesland. Notornis 60: 3-28.